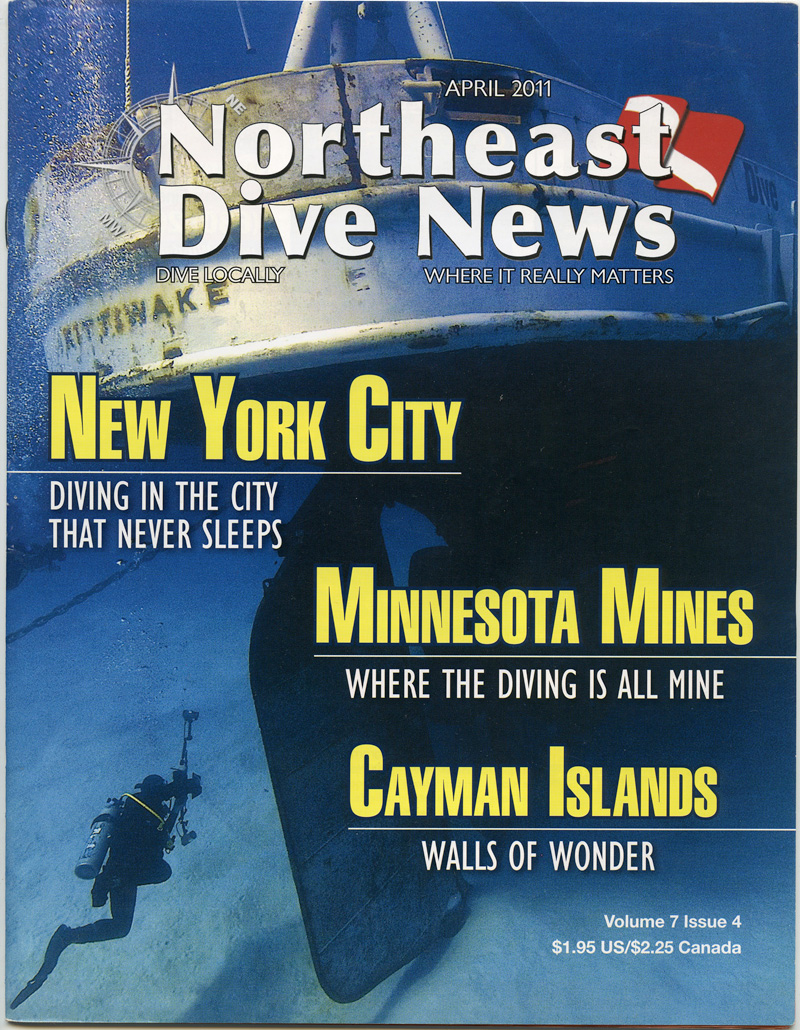

Diving in the City that never Sleeps

by Michael RothschildOriginally published in Northeast Dive News, April, 2011

On a nice summer weekend on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, you might expect to see a few joggers, a line for bagels and lox at Barney Greengrass, or maybe the guy who delivers the Times. It's no wonder I always get a few odd looks from the doormen who see me pushing a luggage cart filled with steel 120s, a dry suit, and a camera big enough for its own car seat down the sidewalk in the early morning.

New Yorkers are very familiar with our city's wildlife – the pigeons that have evolved the reflexes of a cab driver to work in heavy traffic, and the squirrels who hunt for discarded pretzels in Central Park. You would think we would understand that nature doesn't stop at Battery Park. But when I mention to any non-diver (or a typical Caribbean diver) that I like to dive locally, I usually get the same response: "You must be crazy. What is there to see? And even if there was anything, how can you see it through all that gunk?"

Even when I show them a few of the images on my iPhone, it's still hard for them to believe the Big Apple is sitting on the edge of a vibrant, thriving ecosystem in relatively clear water. The reason for this is the water most of us see on a daily basis is in the Hudson and East rivers. And while a public safety diver might be rightly proud of his ability to find a discarded shell casing in a silt bottom by feel alone, I prefer to leave those challenging river dives to the professionals.

Unless we dive, fish or boat, we might forget about the New York Bight, the triangle of relatively shallow ocean just past the five mile wide channel between Breezy Point in Queens and Sandy Hook in New Jersey, where Lower New York Bay empties into the Atlantic. This area is well appreciated by the local diving community for its thousands of shipwrecks; the Bight has been a major shipping channel for 500 years. But even in these circles, the focus tends to be on wrecks, exploration and artifacts. Marine life does occasionally figure into the dive plans on the local boats, but typically just those species that taste good with butter sauce!

While there aren't a lot of tourists from Bonaire or Sharm el-Sheikh coming to the Jersey Shore to experience our marine biodiversity, it doesn't take long to realize there is plenty to see here for the dedicated fish-spotter. Unlike wide angle photography, good close up images can be obtained with relatively inexpensive gear. By shooting subjects just a few inches from your lens port, and by bringing your own light with you, you can get images just as good as any from the Caribbean. Macro photographs aren't really affected by the limited ambient light, the lack of long distance visibility, and the presence of particulate matter that can cause backscatter.

Shipwrecks are densely populated communities of life that dot the floor of the seabed. The countless nooks and crannies of any sort of structure serve as the perfect habitat for the small creatures that form the basis of a much larger food chain. This is the concept behind the artificial reef programs, in which ships and other structures are sunk to provide shelter for small invertebrates and growing fish larvae. The small organisms attract larger fish who hunt them; making shipwrecks attractive to both divers and fishing boats alike. Indeed, one of the main entanglement hazards around our wrecks is monofilament fishing line or even nets. For this reason, be sure to bring at least two cutting devices to any such dive – a knife and a set of shears is best.

You can also find healthy marine life in the New York area without the need to wake up at 3 a.m. to schlep out to Long Island or New Jersey for a boat ride. There are a number of beach dives within reasonable driving distance. While the visibility is rarely as good as it is on the offshore wrecks, this is less of a problem if your goal is to find the little critters that inhabit the rocky structures scattered within a few yards of the shoreline. Since macro photography is far less dependant on visibility than is wide angle, you can enjoy a productive hunt for hours in relatively cloudy water if you know where to look and bring a good strobe.

One of my favorite beach dives (and the one closest to Manhattan) is Beach 8th street, in Far Rockaway, Queens, near JFK airport. Divers have been coming here for years, sharing the waters with the locals who fish from the pier. In addition to native species such as Black Sea Bass, Summer Flounder, Starfish, Mussels and Crabs, in the summer months you can find a number tropical fish who ride the Gulf Stream north along the Atlantic Coast. I have seen plenty of Spotfin Butterfly fish, as well as juvenile Snowy Grouper and Horned Blennies in this area.

While these waters offer terrific dives, several cautions must be observed. First, since the closing of the "Almost Paradise" facility in 2003, divers park on the street and enter the beach through a hole in the fence. This restaurant and diver hangout used to offer parking, beach access, rest rooms and hot showers for a price. Now the diving is free, but make sure to use the bathroom before you arrive – facilities at a nearby public park or housing complex may not be available.

Furthermore, the East Rockaway inlet is a tidal zone connecting the ocean to the Middle Bay waters that separate Long Beach from Long Island. That means diving is, for the most part, only possible at slack high tide when the swift current stops moving for an hour or so and the water is at its deepest, twice a day. In the past, some adventuresome divers would ride the current east to the Atlantic Beach Bridge and back by timing their entry just before the reversal; this clearly added another element of risk to diving in an active ship channel! These days, however, diving in the area around the bridge is not allowed due to heightened security after 9/11.

There are two high slacks a day, with tidal data published in many places online. Look at your work schedule and the tide tables, and figure out your best shot taking into consideration the time of day and traffic. Even then, on more than one occasion, I have driven my gear out to the inlet, just to scrub the dive because of poor visibility. While the visibility can be quite good, it is also very variable and there is no easy way of predicting it ahead of time.

The water is about 35-40 feet deep in mid channel, and the bottom slopes down from the water's edge on either side of the 300 yard wide inlet. Dive flags can alert boat traffic to your presence, but care should be taken to avoid surfacing anywhere but the shallow water near the beach and pier on the north shore. Navigation is easy as long as you are diving without current; just follow the slope to the north to get home. Because of the fishing activity in the area, make sure you have equipment to cut any potentially entangling fishing lines, as mentioned above.

Beach 8th street is clearly not a Caribbean resort, where easy diving is a stroll away and 24 hours a day. But it more than makes up for this by being available for the price of an air fill and a bridge toll, as well as the chance to fit a dive into a busy schedule after a day's work.

I end my local diving days by unloading my car outside my apartment, filling up the luggage cart with tanks, back plate and regulators, draping my dry suit over the bar. My neighbors sometimes ask me where I have been with all that gear. I reply "I just went out for a dip; it was such a nice day."