Louis Rosen's Journal from World War I

Lou Rosen, returning from the first World War. He writes: "Homeward bound. Resting by the wayside on a box in front of a small grocery store. This was after a line fell out for a little rest while marching to the sea at Brest, France, to embark for home."

My father Louis W. Rosen was born in New York’s teeming Lower East Side in 1888 to Russian immigrant parents, the first of nine children. He was already a graduate of New York Law School and an attorney when drafted in 1917.

He was also a typical basement inventor, and prior to the draft had been discussing a camera invention with army officials. The invention described a rapid mechanical automatic transport system for roll film. As a result, while on active duty as a private with the Field Artillery, he sought and obtained a transfer to the Air Force Photographic Division. You will also see how proficiency in the self taught skills of typing and stenography were of mutual benefit to himself and his superior officers.

I must say something about his inventions, which were usually concerned with common household products, like a one piece razor and even a wet tea bag disposer (to avoid soiling the table top) - he never used any of them in daily practice. Not even the camera, which he credits indirectly with removing him from the front line in the war. He never used anything but a vintage Brownie box camera which could not even be focused.

While in France awaiting the trip home after the armistice, he typed two letters home totaling 36 pages, dealing almost exclusively with his experience during the war. Copies of these letters, plus an Epilogue and some photographs, were privately printed and bound in 1920. The original typed letters are lost, but copies of a few sample pages of the book are included in this new version.

Although I always knew that Dad was a World War I veteran, I knew nothing of his book until about age 12. It was am eye opener to me in revealing how he had successfully and even proudly succeeded in coping with a strange and at times fearful environment.

Following the War, he returned to private practice and later served 20 Years with the New York State Department of Law in Albany. His specialty was real property, contributing to the success of the New York State Thruway in obtaining its rights of way.

Nothing could express my appreciation of his personality more than these final words of a speech delivered by a friend and co worker in 1968 upon his retirement from the Department of Law:

"It was many years ago that the outstanding facet of Lou’s personality impressed itself upon me – a facet which made it possible for me to address our guest of honor as 'Lou' – and that was his youthful spirit.

It is not by the white of his hair that one knows the age of the heart or the mind. Age does not depend upon years, but upon temperament. Some men are born old, and some never seem to grow old. Always sensitive in thought, always ready to adopt new ideas, they are never chargeable with fogyism. Satisfied, yet ever dissatisfied, settled, yet ever unsettled, they always enjoy the best of what is, and are always the first to find the best of what will be. Such a man is Lou Rosen. Constituted as he is, Lou is no different today from what he was yesterday, nor will tomorrow transform him from what he is today."

GENERAL HEADQUARTERS

AMERICAN EXPEDITIONARY FORCES

November 23rd, 1918

Dear folks:

The censorship having been lifted to the extent of allowing me to talk of the past and the present, I am taking advantage of this first opportunity to communicate a little account of myself concerning facts not related before. You can take my word for it that it is absolutely true. In telling the story, I shall omit numerous circumstances and events between dates, not that they are less important, some of them more - but that if I took them into account I should never end my letter. My dates will be fairly accurate, as I had no patience to keep a diary of "European Trips".

The same Sunday, April 14th that the boys visited me at the Camp, toward evening a request came in to the Supply Room for a memorandum regarding the amount of cubic space necessary for our luggage, to be submitted at once. It was a sure guess. At the end of that week about Saturday morning we were told officially by the Captain, who himself at the start evinced surprise. During the last remaining days I worked my head off in the Supply Room, as equipment then was the principal thing.

At last, about 3:30 A. M. Monday April 22nd we marched off, while the rest of the world was asleep. I was then all in through overwork, loss of sleep, and even food in attending to this job, and under the circumstances shall never forget the strain in reaching the station in marching order, carrying a full equipment consisting of a pack that weighed about a ton, a rifle, 100 rounds of ammunition in belt, hanging like so much lead around you, rations, overcoat, raincoat, etc., and with that I had the misery of wearing a brand new pair of shoes that were too small covered by rubbers of the truck drivers' type. It had rained all the time, the roads were extremely muddy, it was pitch dark, everything blended with this one setting. I just about kept together, puffing away, and with the break of day reached Hoboken.

After a delay of a few hours, we climbed aboard the good ship Vaterland (now called the Leviathan), the very boat on which Henry Schiffer and I came back when she made her last regular voyage from the other side. That was certainly a coincidence, and little did one of us dream on that former trip, while sitting at the table with napkins and music, that I would be going back on the same ship minus either of them.

The boat did not leave until Wednesday morning. You can imagine, in the meantime, how I felt standing on the deck and looking across the Hudson in the direction of Harlem - no chance to communicate, let alone going home. So near, and yet so far - and it was to be still farther.

A page from the journal with Lou's map of his travels during the war. Click for a full sized image of the map.

The voyage took about eight days, and I must say, so far as the sailing was concerned, it was splendid. Fine weather, and no submarine ever approached us. If any did we never knew it. She was heavily manned, and two days before we reached port we were picked up and convoyed by four destroyers, two on each side, fore and aft. When we got out of the bunk on May 2nd, we found the ship anchored in the harbor of Brest. The life on the boat was a mixture of comfort and discomfort, both in the extreme, but neither of which could be helped. There were about 14,000 troops on board from all over the country. One of the many things that kept us busy was the daily "Abandon Ship Drill". Of course, there was plenty of gossip, such as "the German Government has offered a prize to the submarine commander who would succeed in sinking this capital ship." The thought of that was a cure for seasickness (and nobody was sick).

On May 2nd, we marched off the boat and right up to the "resting" barracks in the heart of the town. Along the road women wept, waved, and what not. To the kids, it was a picnic. They kept following us, asking for chocolate and cigarettes.

The barracks referred to were really used by Napoleon's soldiers, and here and there were interesting sights, where executions had taken place, etc. The walls had about one hundred layers of calcimine, each denoting a certain epoch in the history of France. We stayed there about a week, and around May 9th started off for the training camp.

The trip consumed about four days and nights by train, until we reached the spot, about fourteen miles from the City of Bordeaux, - Camp De Souge. We journeyed in the box cars, labeled as they all are, "Cheveaux 8, Hommes 40"- meaning capacity either for 8 horses or 40 men. The floor was our seat, bed, recreation center, library, dining table, and clothes closet. Outside of that. we had plenty of room for one toothpick. Well, as the expression went, "C'est la Guerre", it is war.

When we finally got into Camp De Souge, I must say that I was agreeably surprised. It was a former French military camp. built on permanent lines, even unlike Camp Upton, well laid out, and had the appearance of taste and beauty. There we received the real training, although it was necessarily very much cramped. All of us, including officers and men, went to some school. For the Headquarters Company, whose duty was to attend to the technical work in connection with the batteries, the lessons were in the installation of telephones. telephone lines, and switchboards, and the maintenance thereof; also in radio work and firing data in connection with the guns. Miniature telephone lines were also set up. Toward the end, actual firing was done with the guns on designated targets, barrage practice was had, etc. However, I busied myself around the Supply Room, as my ambition was to get into the Air Service, steps for which I will explain later.

Our stay there was about two months. During that time, I was on two Sundays in Bordeaux on pass, and it was indeed a treat, after all that isolation, to get into a big city. At the beginning of the stay, right after I received a reply from The Adjutant General to Eddie, forwarded to me by Ed, I took up with my Captain the proposition of sending an application through military channels to The Adjutant General, A. E. F., asking simply "to be allowed to appear before the main Photographic Bureau in France to show and explain my invention", and in words to the effect "be judged according to its merits". I figured that was the best stepping stone, and it showed that I was not bluffing. I annexed the letter Eddie sent, also two sets of pictures that I luckily had, stating the experiences I encountered in the states, making the question very clear as to the merits, and giving telling proof by the pictures enclosed.

Images from Lou's patent application for a film advancement mechanism. Click to read the original patent.

By that time I stood very high in the estimation of the Captain. I had a heart to heart talk with him at his private quarters, and he confirmed to me the experience at Camp Upton, that he was prohibited from entertaining any application whatsoever for a transfer and under Division Orders could make no exception, as they in turn were acting under secret orders from the War Department, which later I learned were to the effect that the 77th Division was to be ready for overseas duty. However, now that I was in France, my environment was different. The Captain told me that he would speak to the Colonel of the Regiment about it, and he did so, getting the application to be sent off with recommendation for approval. In connection with the captain, I will say that I won his opinion in the last few days' of sleepless work I put in the supply room at Camp Upton - a time when he was almost always around, being anxious to have everyone fully equipped in time - and then through the work I put in, on board the Leviathan. The company clerk became seasick, and he called upon me to make up the pay roll and muster roll, a long and very tedious job. It lasted about five days, and I banged away on the typewriter in a Royal Suite on the ship. Special permission was given to work in there by one of the ship's officers acquainted with the captain, as otherwise there wasn't an inch of extra space. When the work was finished he paid me a very high compliment in the presence of the staff in his private room, saying it was the best he had seen - (ahem). In the course of a little conversation in that room he asked me if I had any touch of seasickness and how the voyage affected me and I then took occasion to tell him that I was on the very boat on her last passenger trip to the Slates and so felt perfectly" at home"

During the course of my stay at Camp De Souge, near Bordeaux, France, I must recite some little experience I had with horses. At that place, word came to us that, contrary to our expectation, the guns would be of a different type, horse-drawn and not motor-drawn. Also, nearly all of us would be mounted. Immediately, those of the Regiment who were "farmers" became more popular then the "would be chauffeurs". Details of men were sent all around the country to bring the horses in as they were bought up from the French, and there was a steady stream of them coming into Camp De Souge after a while. En route, these horses traveled in the same class we did, but evidently a horse can't stand it and when they reached camp a lot of nursing was needed to round them out.

We had two lectures on how to take care of them. These were improvised, as the subject of horses had not been anticipated in the States. At the first lecture, we were assembled around a wall on which someone, unseen, drew a picture of the beast for illustration. It was a good thing every part was named in writing, at that we had to use our imagination. The lieutenant who delivered the sermon was the best expert who could be found on such short notice - I think he once hired a horse in Central Park. One of the first things impressed upon us was to treat the animal with kindness. To a large extent, this was followed out later to the very letter, because we never were fed, until we had first fed the horses, and they had a "rub down" much more frequently than we had a bath. But otherwise it was a good thing those horses couldn't understand English or the little French we knew. A few days after the lecture we were marched up to the stables for lessons in equitation - cleaning, feeding, watering, harnessing, mounting, riding, and other things. Twenty of the most amiable horses were chosen for the purpose of instruction. The superlative degree that I use is not the clearest indication of their tameness. They were tamer than that.

I went over to one beast, patted him 3 - 1/2 strokes on the back, according to instruction, the Army having discovered that that was a friendly way of introduction. I stood on the proper side, according to instructions. I held the reins with the proper fingers and at the proper angle. I did nothing that was not in the lessons preached to us. At the command "mount" I jumped on his back (we had no saddles then) feeling certain that as a good student I had full control of the situation. We were then to go around in a large circle. At the command to go we started off. My horse covered just about two degrees of that circle, when up he went. I tried to hold on, but his back was so slippery that I was thrown to the ground. I was all shaken up, but nothing broke. It flashed through my mind that the horse becoming Louis-less, would run away, little thinking that there were others around to check him. I jumped up to get him, but just then a lieutenant intervened with the admonition "don't run at him like that, you scare him, approach him gently". As I started to get him, an Italian fellow in the company, thought he would like to take a chance with the devil. He was accustomed to horses, evidently being a member of the D. S. C. society - ante bellum. No sooner was he on his back, when off he went in the direction of Berlin (must have been a spy). But he managed to cling to him, and both came back to the prescribed circle alive.

We were at this camp for just about two months when word came that our period of training was over and that we are off to the front. Just then the Germans had made great inroads and the tide was very much in their favor. That was about July 12th. A Table of Organization was quickly gotten up as to what each fellow was to do in the line which he had demonstrated. Against my name, was placed the title "Battalion Commander's Instrument Operator". This B/C Instrument, for short, is one for sighting targets and results of fire. At that, we had no occasion to use it, as the fighting that developed later was largely through map work and airplane reconnaissance, In theory, the Major (who is the head of the Battalion) operates the instrument and I beside him, record results, and I also, presumably, take care of it when not in use. When the lists came in, they also contained checks as to who are to be preferred with horses, there being a shortage at the last minute, quite a few of them having become sick and some died. My name sure enough, had a check.

A day before we started off for the first front, I went, with the rest to the stable and picked out a brand new outfit for a horse - a beautiful McClellan saddle, etc. Also leather grain bags, feed bags, and what not, even a manicuring set (curry comb and brush). The theory of that long-titled job is that I ride up on a prancing steed with the instrument to any observation post the Major chooses, and naturally he having a horse I couldn't run after him on foot. In getting my equipment ready, I went so far as to fill up the extra bag that is carried for that purpose with oats. All I needed was a horse. They were to be picked the next day. If that "a horse" only knew what I had for him. During that night, some more horses either got sick or died and when the next day came, there wasn't enough to go around on the pick, and of course the privates had to give way to the noncoms, so supposedly I was out of luck. Well, I never got a horse since, and as for the B/C Instrument, the Major never used it. Somewhere in France there presumably lies a harness equipment that has not yet linked rider to beast. May the bond which it will eventually bring see both of them plowing the ground, with the proverbial sword as the plowshare. So I still know little about horse riding.

To continue, on July 12th we started off for the front. We were always in mystery as to where we were going and what was actually going to happen. That in turn, bred a lot of gossip. After a few days' trip we detrained at Baccarat, on the Alsace-Lorraine front. The town had before been shattered to pieces, and in the early morning (everything of that sort happens in the midst of the night or in the early morning) we marched through it. An additional article of equipment was the steel helmet given to us on the boat. As we marched to our position, the firing on the front could be distinctly heard and aeroplane duels above us were not uncommon.

We were on the Alsace front for just about two weeks. There we came together with our infantry, which had traveled by way of England. One evening, I happened to be in a little grocery store "epicerie" in the town of Neufmaisons (near the Alsace border) when I saw a fellow of the 308th infantry. Without regard to the number of men in the infantry, I asked him if he knew Charlie Zucker. "Sure", he said, "I worked with him". And so it was, he conducted me to the little town where the infantry was stationed and there I met Charlie. It certainly was a happy reunion, but we were too far apart to get together again.

Lou Rosen in his "doughboy" uniform

For the purpose of actual field work, our Headquarters Company was split up into a Regimental Detail and a detail with the First, Second, and Third Battalion. Batteries A and B, formed the First Battalion, Band C, the Second, and E and F, the Third. The Commanding Officer of each Battery is a Captain, of the Battalion, a Major. The latter would give the firing orders and instructions to the two batteries under him. The Headquarters Company were "the brains of the Regiment", so to speak, and supposed to contain the best technical men. We took care of establishing and keeping up telephone communication to the batteries, etc., a very important function in the process of artillery fire. I was assigned to the Third Battalion, Batteries E and F. Our detail consisted of about thirty men and we had our own little field stove and cook. In the first three days on the Alsace front we set up, and thereafter maintained, about twenty miles of wire, and it was some job, leading them to the batteries, between batteries, etc. In addition, among our own bunch we had guard duty, which consisted partly in standing by the telephone switchboard during the night, installed under a clump of trees. I had my share at that a few nights, and a little thrill and experience went with it which I shall describe at another time. I bet you would never have recognized me as I was dressed on those occasions - a winter overcoat, a belt full of cartridges, a loaded, 45 caliber Colt pistol on my hip, a tin hat on my head, a gas mask against my breast in the alert position and a wrist watch on which I continually looked for the time when relief was up.

The rumor that we were to stay on this front a few months was hit on the head at the end of two weeks. The gossip then was that we were going to Italy, somewhere in the mountains, evidently because we had turned in our summer underwear. The next morning, when I got up from my tortuous sleep in the box car, and compared the passing towns with the map, I found we were headed straight for the Chateau Thierry front. That was corroborated by the absence of any smell of garlic we all expected to be infused into our atmosphere after a while. As usual, we started and finished in the middle of the night. All the detail in connection with this moving taxes one's energy to the utmost and keeps one awake all the time. It was a case of no rest for the weary. The horses especially, took up a lot of time and attention.

We detrained about 25 miles southwest of Chateau Thierry at a station called St. Simeon, about 7 miles East of Coulommiers, but at that time, owing to the push started not very long before, the front was about 45 miles away from that particular station. Well, the hike to cover most of that ground lasted three days, walking all through the night and "resting" by day. I shall never forget that. The first night they were ambitious, and with the packs on our backs we covered 20 miles up and down hills. In short time the battle area was around us and we passed in the darkness of the night, through town after town, in which almost every house was battered to pieces. As we progressed, we came upon places that were fresh in their testimony as to what happened. We were immediately in the wake of the Rainbow Division etc., that had started the push back from the Chateau Thierry point. The many gruesome sights that I have seen in this battleground I shall relate at another time. During the day rests, so-called, we camped at Belleau Woods and on one of the days right on the bank of the Marne about 5 miles from Chateau Thierry. The sun was then strong, and despite my sleepiness and weariness I went into that historic river for a swim. It s something like the Neversink, only a little wider and deeper. It took me a little time to get accustomed in that section to the smell of lime, decaying matter, and the odor of the dead. At first it was nauseating.

Well, to cut the story short, we finally got into position near Fismes, directly north of Chateau Thierry and right between Soissons and Rheims. The Boche was still very near those two latter cities, but the strongest point of resistance became the center where we fell in. He had taken a definite stand on the Vesle, and also the nature of the ground at that section gave him a decided advantage. Before the final dart into battle line, we camped near the edge of a woods about four miles long, which distance, with a little more stretch, separated us from the line. The three nights we thus camped were as sleepless as they were exciting. No sooner would it get dark then there were air raids by the Boche, bomb dropping, gas alarms and what not. A regular Fourth of July. The steel helmet, gas mask and I were like the Three musketeers - inseparable. In fact, I used the tin derby for a pillow and the gas mask for a blanket. On the third night, half of the guns from each battery and half of the personnel went into position. All in our bunch went along, except three fellows and myself, who were told to remain to look after the horses not needed to go into line. The following evening, however, our Major came back in his motor cycle, and left word for me and another fellow to get up to the line that night, as we were very much needed on the telephone work. We were to find our way by following the remaining half of the guns and personnel of the batteries. His chauffeur, in the meantime, gave us a brief account of what was going on, and it was not very pleasant news. In the trip of the previous night he himself had escaped a large shell by a few inches and after my own bunch had reached the headquarters and been in the farm for little while, a shell came clean through the roof and landed in the next room, killing one and gassing a few others. Also, some of the horses had been killed by shell fire.

With the above information, I started off for the line. The batteries we were following were going to a position which was not exactly where our Battalion headquarters was stationed - just a little distance away, and this other fellow and myself got into a ration cart that was to stop a little closer to our position than the guns. The moment those guns pulled in they got right into action. We started off about 9 P.M. The vehicles kept about 50 feet apart all the time to minimize the damage by an exploding shell in our midst. As we emerged from the other end of the woods we still had a little stretch to make, but the itinerary had to be changed. The M.P. stationed there informed the vanguard that those roads were being heavily shelled at that time, and we certainly could hear and feel it so we had to make a detour.

About 12 P.M., the ration cart finally found the spot what was thought to be its prescribed stop - beneath a large open shed near the road. Well, let me tell you, for about a mile before we reached this shed all of us had fallen about a dozen times flat on the ground to escape the shrapnel of bursting shells all around us (through the woods we felt ostrich-like safe) and it wasn't a bit quieter at the shed. From the shed, our headquarters was supposed to be a distance of about three blocks. But in the thick of the night, with shells flying from directions we were not yet familiar with, we were not going to get lost looking for that barn. An M.P. came up to the shed and told us that if we intended to remain there one of us should be chosen as guard against gas attacks as there had been many cases of it in that section. No one volunteered. everybody was all in and sleepy, and being a mixed bunch, there was no organization. I lay down under a wagon on a pile of dirt underneath the shed, I in my clothes of course, intent not to fall asleep, but to rest up. Just then a piece of shrapnel tore down an edge of the roofing on the shed. It was that indiscriminate firing for general effect and no one could tell where the next shell would land. About 10 feet away from our shed another unit was putting in place a 6 inch rifle (cannon). It is a long range gun for shelling back areas and they worked fast (cussing and swearing) to get it in place under cover of darkness. Pretty soon it commenced to fire away. Despite its proximity and noise, and the noise of the general firing around us and bursting shells, and my intention not to fall asleep, I did doze off, so tired was I. All can say is that the Lord kept watch over me, and very early in the morning I got up and was able to stretch. One of our crowd came from the barn and showed us the way up.

The barn, called La Pres Farm, was a large old fashioned farm, dating back to an early age. The buildings were of heavy stone walls, consisting of four wings, forming a square, in the center of which was a large courtyard. There were also various outhouses. It is needless to say that everything was not spic and span there. Some of the infantry of our Division occupied most of the wings - those fellows who were immediately to go into the trenches a little distance away. Only one wing was used for our crew. The batteries were stationed at the edge of a woods about 500 feet away from us, right across an open field somewhat hilly, sloping up in the direction of the guns. My duty in the telephone squad was to help maintain communications at all times between the guns and our Battalion Headquarters (where we were) and certain other positions. It simply meant that every time wire was broken by fire we would have to go out and find where the break was and splice the wire to re-establish communication. We would do this in turn, but the breaks happened so often that one was sure to go out about twice in 24 hours.

When I got into that barn that early morning, I was still tired and laid down on the floor and fell asleep (a regular tramp, by gosh). In about an hour I was aroused to go with a lieutenant to patch up some wire. We went to that field referred to. By the light of the sun I became more acquainted with that terrain. There were two roads, one passing on each side of the field. While we were at work one shell after another landed in those roads. This lieutenant is a lawyer (and who I just learned, was subsequently sent back to the States to teach some of the recruits) and he said to me "a fine job for two lawyers," But he had the will and spirit. We got through with the work in good shape.

In the barn. our sleeping place was in a deep cellar, and where we also transacted all our business by candle light, the switchboard being located in one corner of it. My clothes never came off. The very first night I was called out about 1 A.M. with another fellow to find and repair two breaks. With heavy shelling going on, we just felt our way by a pale moonlight over that field never knowing when the next shell would land near us, patiently trying to find the trouble. Heavy firing was going on and at that time, several ammunition dumps of the Germans had been blown up, giving the reflection of the blaze as to make it seem that our own woods were on fire. Some night! The way to find the break is to get hold of the wire at the switchboard and let it pass through your hand as you walk along, picking it up somewhat from the ground. The wire is just laid on the ground. After we find the break and repair it, we tap in on the wire to see if the connection is perfect and in working order. We found the trouble that night, fixed it, and came back unscathed. The next day, in the afternoon, I went out again with the same lieutenant. We were away from the farm not more than 200 feet when a shell whistled right over us and landed square in the courtyard of that farm. After we came back we found that two fellows were killed and several wounded. Those shells do leave some holes in the ground. At another time, the Huns had gotten the location of some of our batteries, and a regular duel took place. It certainly was exciting. Two of the battery fellows were then killed and several injured.

The first aid station was in a room in our wing to which ambulances were continually called. And some sights, once more. As was to be expected the infantry was the principal sufferer, and I saw those doughboys coming in one after another gassed with mustard gas.

The happy climax, so far as I was concerned, came on the fifth day of my presence at that battling farm. At about seven o'clock in the evening, there commenced to land right up close to our building one shell after another - deliberately aimed at us. The walls actually shook. We were all huddled together down in the cellar. The Huns had evidently discovered the importance of the target being Ballalion Headquarters and where most of the lines were. If there had been a direct hit over us, we might have been buried alive under the fall and weight of those stones. The shrapnel, however, could never have entered those walls. At least, fifty shots were fired in rapid succession. and then it subsided to a much slower pace. Probably the next day, as was the case after any special firing, a Hun aeroplane would fly around to find out what damage had been done. Invariably, we were never left alone during night time, the firing being increased then. As a result of the very heavy firing just mentioned, some of the lines were already broken as no connections could be had from our switchboard. I saw visions of being hustled out shortly to do some fixing.

While engrossed in the said vision. I heard my name called from the other end of the cellar where the Major and his Adjutant were. I walked in, and the Adjutant said. "Rosen, you are going out." For the moment, it appeared to me that I was being sent on a dangerous, important mission in connection with the firing. The chauffeur standing by then told me that I was going with him. I asked him where. He said "you have been ordered back to the Headquarters of the S.O.S. (the rear) and I am to take you to Regimental Headquarters in the adjoining town, where you are to get a copy of the order, instructions, etc." Even then I could not fathom the significance of the whole thing, as I had long given up hope on that application - never having heard from it. Well. I gathered my belongings, and with it slipped into the side car of the motor cycle. He went through the roads like lightening; the firing was going on all the time. I reached Regimental Headquarters, about two miles away, and the Captain gave me an official copy of the order that came through. It read as follows:

"GENERAL HEADQUARTERS, AMERICAN EXPEDITIONARY FORCES.

Special Orders No. 227.

France

15 August 1918

Extract 81

Private Louis W. Rosen, Headquarters Company. 306th Field Artillery, will proceed to Headquarters, S. O. S., reporting upon arrival to the Chief of Photographic Section, Air Service, for showing and explaining drawings of his invention, and upon completion of this duty will return to his proper station. The Quartermaster Corps will furnish the necessary transportation and subsistence. The journey directed is necessary for the public service.

By Command of General Pershing,

James W. McAndrew, Chief of Staff."

The compliance of that order was left to me. That same night I got into a ration truck that went back through that woods to fetch food for the next day. At the end of this journey I remained in the truck and slept there until morning. Then I got out, cleaned myself a little, brushed off the dust of battle (although I still wasn't very far from it) and remained around until after dinner, eating with the Supply Company. Then I got my pack together and started on my way.

The journey certainly was very interesting. First of all, I had to get away from a large war zone, recently the scene of much conflict, meaning a stretch of many miles before I could reach a spot where there was railroad transportation. At any rate, I felt like a bird that had just left its cage. For the first time there was no officer at my heels to tell me which way to go, how to breathe, when to rest, etc. My destination was the City of Tours, some few hundred miles away from strife. I got to the main highway, jumped on a passing truck and away it rattled, the din of the shooting becoming fainter all the time. I figured I would get off at Fere-en-Tardenois and there find a Quartermaster who would furnish me with rations, etc., for the journey. When I got there, no such unit was in town. I questioned an M. P., and he confirmed this; he also told me that I had better be off the street before night, as all stragglers were picked up. I looked him square in the face and said "0h, I am not afraid of that, I have an order from General Pershing, which will take care of the situation”. He thought he was wise, but with that order in my pocket I was there with the "bravery". It was interesting to go through the town and see some of the French inhabitants return to their shattered and abandoned homes. There is hardly a building left untouched. Bullets and shells must have poured in these regions.

Transportation ticket issued to Lou Rosen for travel from Chateau Thierry to Tours. "No. 2" in heavy black crayon specified a second class ride.

The trip to Tours from Chateau Thierry was in the direction of Paris, and I had fond hopes of stopping off at that latter city. But there was a confusion of trains, with the result that my train stopped at a French military detraining point about two miles before Paris. If I were able to speak a little French, I might have found my way to Paris, by some shuttle train or the like, but I was traveling like a dumb animal, unable to converse intelligently in any language that I knew. I was always delighted to let well enough alone. In that respect I was worse off than when in Germany right before the war with Henry Schiffer, and had to eat boiled eggs simply because we couldn't express the term "fried" eggs either by word or motion. Then again, the pack on my back made it very uncomfortable to maneuver around. So from that spot I branched off to Tours. It was, all told, a long ride, and I reached Tours about 3 A.M. There is a large A. E. F. desk at that station, in grand style, because the city is the headquarters of many branches of the service, practically everything except General Pershing and his staff departments, the latter being where I am now, in Chaumont. After registration at the depot I was escorted by an M.P. to a temporary barrack and slept there until the following day at 12 noon. Then I commenced to hunt up my man and department.

I located the office in Beaumont Barracks, at one edge of the town. It is the cleanest place I have seen, built also on permanent lines, and for the time I was there I really enjoyed it. It didn't have that mob. We also had our own YMCA within the grounds where there was plenty of elbow room and silence. The meals also were grand. At first it was a strange reaction after all that I had been through and I could hardly believe myself, so suddenly did it happen.

When I called at the department, the officers told me that the chief of the Photo Section, Captain Steichen, was in London, and would be back the following day. In the meantime they chatted with me on the subject and treated me royally. They knew all the officers and departments I had dealt with in Washington - themselves members of that clique - also told me that Captain Ives had come to France, the very officer who had been experimenting with the camera in Washington, and I certainly felt big in that environment. Anyone who knew or got to know about the invention handled me in good style. At that place this matter touched home. I met Captain Ives a few days later for a short while and he still had the same high opinion of the matter, expressing regret that I was unable to get to Washington and stating that he still thought that I ought to be there, where the facilities were best, but that for the while the matter had better take its own course.

Staff at Photographic Headquarters, Air Service, A.E.F., Tours, France. Click for a high resolution version.

He then took up with me the matter of joining his force, stating plainly that I belonged here rather than there. He said that under that order he could keep me with him on temporary duty (while I still remained a member of the F.A.). In the meantime, however an application was to be put through for my permanent transfer. During the course of my conversation he made me tell him all that had been done with the camera and showed sincere interest in my activities. He volunteered the statement that after the matter had been settled he would put me in line for promotion. The application for transfer was then and there drawn up by his personnel officer, and here is the endorsement that was put on it:

" Hdqrs. Air Service, S. O. S., A. E. F., Office of C. A. S., Photographic Section, Aug. 23, 1918. - To Commanding Officer, Hdqrs. 306th F. A.

I. The Photographic Section is very much in need of men with the ability this soldier shows, and therefore approval is recommended.

2. Soldier is now on temporary duty at these Headquarters where he was sent on our request, for the purpose of showing his plans and to explain the working of his invention.

3. This camera shows great possibilities and if soldier can be transferred to the Photographic Section where he will be given every opportunity to improve and develop his invention, it is believed the transfer will prove of benefit to the service.

By authority of Col. Chandler E. J. Steichen, .

Capt. A. S. Sig. R. C. "

You see, before I was ordered down there, the matter was evidently referred to him for what it was worth, and he OKed the proposition to have me appear. In fact, when I showed up, there was a folder in his personnel file all ready with papers in my case. That in a way explains why it took me so long to get action.

I remained in the photo laboratory about six weeks and learned a whole lot about the work and the present cameras in use. I enjoyed the City of Tours immensely. It is a beautiful place and very historic. From the the latter standpoint it is the oldest city in France, and everywhere there is something of intense interest. It is the birthplace of Balzac. The beautiful Loire river passes on one side of it, with castles here and there. In the suburbs I have visited places where the monks used to live and worship in caves, visiting the cave where St. Patrick studied, etc. Then there are famous cathedrals in history going back as far as 1500 years - St. Martin. Charlemagne, etc. There are spots where kings and queens used to live, for at one time it was the most attractive city and crowned heads traveled from afar to visit it. It was also the great center of Christianity. I had plenty of time to see those spots on Sundays in conducted tours from the YMCA. Luckily, I was there during the holidays, and enjoyed a real, home-fashioned worship in a real synagogue.

My romance was not yet ended. About September 28th, while this application for transfer was still in military channels. I received a letter, delayed in mail, from the Captain of my regular company (Hq. Co., 306 F. A.) enclosing a copy of the following order and a letter written by him asking that I comply with that order:

"HEADQUARTERS THIRD ARMY CORPS, AMERICAN EXPEDITIONARY FORCES

France

Sept. 2nd, 1918

Special Orders No. 78. 3

Under provisions contained in Paragraph 114, Army Regulations. 1913, Private Louis W. Rosen (1715213), Headquarters Company, 306th Field Artillery, is transferred to Headquarters Troop, this corps, and will be sent with the least practicable delay to these headquarters with instructions to report upon arrival to the Chief of Air Service for assignment to duty.

The travel directed is necessary for the Public Service.

By Command of Major General Bullard:

A. W. Bjornstad.

Brigadier General, G. S. Chief of Staff."

This Third Army Corps order was mysterious to me. I was never able to discover what really originated or prompted it. I learned that the 77th Division, of which I was a member, was included in the Third Army Corps at about the time I asked for the transfer. Evidently the papers had to pass through the corps for approval, and some officer in learning of my ability had me preferably transferred so that I could be with the local Chief of Air Service of his corps using the authority of the law quoted in the order. I never could find out who that officer was and when I met the Chief of Air Service of that corps, he was a new officer on the job anyhow. Well, the order had to be obeyed, so it was thought advisable that I make the trip and see what's what and try to get the matter corrected.

I left on October 2nd, just after I received the money from home by cable, which came in very handy, taking with me 150 francs of that money and leaving the balance of 600 francs on deposit with the American Express Company in Tours. On account of being away on pay day at each particular place, I missed three months' pay in succession, which was then due to me. I also took with me a copy of the papers on request to be transfered to the Photo Division, with their endorsement, etc. I felt sure I could straighten the matter out and return to Tours.

My trip again was in the direction of the front. I did not, however, expect that I would go as deep as before. These Army Corps embrace about 4 or 5 Divisions (approximating about 160,000 men). The Corps Headquarters keeps pace with the advancing line within a reasonably safe distance, though the the latter is not always a sure thing. To find the unit, I had to stop off at St. Dizier, a regulating camp. where all casualties, those evacuated from hospitals, stragglers, and men and officers of every kind and description are corralled for the purpose of distributing them to where they belong or where they are ordered to report. The scene at that camp I shall have to describe at another time. It is a mixture of all elements. I spoke with many of the fellows of the famous Divisions that had seen the fighting from the start, the 42nd, 32nd, etc. most of whom were returning from hospitals, and heard some stories.

The officer in charge at that regulating camp did not know where the Hq. Troop office of the 3rd Army Corps was, at the time I inquired, and it took him until the next day to get the information. In the meantime I had to sleep on a bench overnight. For rations, while waiting to be sent off, they give you a slip with which at a certain counter you get two boxes of hard tack, a can of beans, and a can of corned willy. This is for one day. Of course, it is all eaten cold. There is no kitchen there. The next night, with directions in hand, I started off, at about 9 P.M., on a train of about 50 cars, containing fellows who were to branch off to the various towns for their respective divisions. I was to go to Nixeville (near Verdun) and get off at Lemmes the nearest point, a few miles away. It was some trip, the train just barely crawling along. To get to the regulating camp my train, mind you, consumed 15 hours more time than the schedule called for, and from St. Dizier the pace was even slower. Gradually the roar of the front became louder and louder, for we were hugging the Argonne sector, and at that time, right after the St. Mihiel drive they were banging away to extend their gains in the Argonne Woods, and near Metz, all of which could be distinctly heard.

I got off at Lemmes. as directed. The place was rather dismal, the air chilly, the sky cloudy. Not knowing what was in store for me I had a mingled feeling of perplexity and romanticism. In my hands I held an A.E. F. edition of the Herald of the previous day, in which the headline was "The Americans made a noted advance yesterday in the Argonne Woods, with new troops of General Bullard's Third Army Corps in the lead." I asked a soldier where the headquarters of the Third Army Corps at Nixeville was, and just how to get to that town. He said "you might save yourself a useless trip by asking the Town Major over here just where the corps moved to, because they went into position the other day, and I am sure you won't find them at Nixeville." That seemed to confirm the news in the paper. I began to wonder whether I wasn't chosen for the front lines again, but the order had a certain singularity about it that calmed my suspicion. It was cold, so I commenced to walk on the main highway, the Verdun road, until I was actually about a mile from the City of Verdun. Then by a happy chance, necessitating a little retreat, I found an old shanty that housed the office of the Headquarters Troop of that Corps: Because of the delay in mail in receiving that order, as stated before, I was about a month late in reporting on it, and the sergeant didn't know what to do with me. In fact, he didn't know why I was transferred.

He had on file my service record, and by a happy chance he had just finished typewriting the payroll, so I slapped my signature down for the three months' pay. That was something gained. The decision was that I call up the Third Corps Observation Group, a branch of the Air Service operating with that Corps, stationed at Souilly, a few towns away. This town also happened to be the advance Headquarters of General Pershing during the big drive. I did call up and came down there by appointment. I convinced the Adjutant over there of my standing, and he became satisfied where I belonged. However, he said the mailer would have to be taken up through the Chief of Air Service of the Corps, and to whom I was really to report under that order, but had not yet found where he was. These staff officers are separated in many instances among several towns in the same sector. The Adjutant asked what I could do to make myself busy in the meantime, and I told him I was good at stenography and typewriting. About two days later an officer of that Observation Group took me in an automobile to a nearby town called Rampont to report personally to the Chief of Air Service of that Corps. His name is Joseph C. Morrow, a colonel coming from Pittsburgh. These local chiefs, of course, are subordinate to the Chief of Air Service of the entire A.E. F., at G.H.Q., where I am now. The officer over here is a Major General.

To continue, I wish that I had a picture of the place where I was brought. It was a beautiful chateau or bungalow, call it what you wish, on a hill overlooking a beautiful valley. It had a balcony all around and a little lawn in the front. Its only occupants were the Chief of Air Service before mentioned; his aide, a first lieutenant; a French officer assigned to infuse us with their methods; a Private, as orderly, and a beautiful black dog, the pet of the family. There were wires running to the house and connections could be had with almost anybody. Now a colonel, let me tell you civilians, is a high ranking officer. He tops a 2nd and 1st Lieutenant, a Captain, a Major, and a Lieutenant Colonel. The rank above him is Brigadier General. It was night time when I was shown into his room. After I was introduced to him by the officer who brought me up, he said "You are a photographic expert, I understand." I replied, modestly, "Oh, I have just invented a mechanical device on the camera for automatic movement of the film." And said he, "Captain Steichen had asked for your transfer", etc. (He must have gone over the papers I submitted to the other officer before calling for me). I told him just what my situation was. Then he said, "I understand you can handle a typewriter." I told him I could. He then said, "It will take about a week to straighten your matter out so that you can be sent back, in the meantime you can make yourself at home over here and stand by with us." I was given a spare bed room right next to his chamber (mind you, a bed room), and did "stand by" for two weeks, The life, up there was very interesting, and I shall explain that another time. The activities took in all the aeroplane operations in most of the Argonne sector and on the Meuse, and all through the time that the Americans were hammering and bombing away which culminated in the final thrust started on November 1st and which then brought them as far as Sedan. What I did and the information I waded through was of a highly confidential character, very important and of course interesting - plans both before and after attacks.

Close to November 1st the Colonel came back from a conference at Corps Headquarters, and said that General Patrick, Chief of Air Service of the A.E F., was around and signified his intention to appoint him Chief Inspector of the Air Service, a newly organized department. The next day the Colonel called me over and asked me whether I wouldn't prefer to go with him to General Headquarters on this new job. I made a good impression with my work, and my proficiency was evidently the cause of his quietness on his promise to straighten the matter out with the Photo Division. Well, in the channels I was in, I became satisfied to let matters take their own course, having become somewhat tired of continually straightening out red tape. At least in this instance, especially after being coaxed, I was on the right path or rather on a pleasant path. I consented. He then sent his lieutenant up to Corps Headquarters and in no time had me transferred to the Air Service. Before that I was a member of "Hq. Troop" and assigned to the Chief of Air Service for duty. The next day he left for Chaumont, the home of G. H. Q., with arrangements to send his big Cadillac back for me the following day and also to fetch some of his belongings left over in my care. While I remained, his successor moved in with a larger staff. It was that first subordinate air unit I reported to. I helped them out in a little work. The result made them anxious to have me and feelers were put out about my willingness to remain. At the same time, I was asked by a lieutenant who expected to be put in command of a squadron - the aide referred to - whether I wouldn't keep him in mind. In either instance I would have become a sergeant major. But I was with a colonel, going to General Headquarters, and wouldn't entertain such ideas.

The next evening the car came back, and off I went via Chaumont, a distance of about 90 miles. We started too late, so after a long stretch we stayed over night in a barrack at Colombey-les-Belles, a very large Air Depot, principally to get some little things, and in the morning resumed and finished the journey. You should have seen me sitting back in that big car. I was amused at the many instances of salute by soldiers passing by, thinking that I was an officer, the car going too fast for them to discern the contrary. At one time, a company of about 10 Negroes braced up at attention and snapped their hands to salute as we shot by.

When we got to Chaumont the car pulled in to the big open space in front of Headquarters Building. I went up stairs and there was the colonel already at his desk. I wasn't there 10 minutes when off he went in the car to Paris. In the meantime, I busied myself starting shop. Since then, he has been away and back several times to get his personnel picked. The Table of Organization calls approximately for about 3 Lieut. Colonels, 4 Majors, 14 Captains, 11 First Lieuts., and a few Second Lieuts., all under him and then a host of enlisted men (those not commissioned officers) over whom I am to top as Sergeant 1st Class. The work is to cover the entire Air Service here and in Italy, and you can imagine how important the office is.

But just about the time when this thing was getting whipped into shape, peace was declared, and now everything is being held in abeyance, nobody knowing just how far to go. Of course, we are keeping together as evidently some kind of organization will have to be maintained, but time will tell how broad the work will be and far up I will go. I am not a bit disappointed because it is all the result of peace, and I would have foregone much more than this contemplated honor for such an event. In the meantime, I am taking life easy. To anybody who has been disappointed for some reason or other, they now retort, "est la paix", the French saying, "It is peace".

Now the question is, when I am going home. The answer is,. I don't know, and I am afraid a lot of good and bad luck will enter into that last bit with most everybody. But no doubt the authorities are trying to be square. I don't suppose I could now travel back with the 77th Division, being no longer a member of it. It seems to me they will go home early, as we were the first National Army Division to come across. The papers had that this Division had reached the most northerly point, at Sedan, when fighting stopped. In fact my Third Battalion referred to before, was the first to fire a National Army gun at the enemy, on the Alsace front. A fellow wandering around in Baccarat, was picked up and questioned by the Intelligence Department. He turned out to be an escaped German. He revealed that right opposite our lines was a church used by the Germans for an ammunition dump. We pulled our guns out and shattered it to pieces and the flames around it left no doubt of the truth of the matter. It was the first shot.

They are forming here an A. E. F. band. The best are being picked from each Regiment. The 306th F. A., has been drawn upon for three fellows, whom I have met here and from them have learned a good deal of how my Regiment fared after I left them in August. If a certain story is true, then I am a lucky boy.

As I said before, there are many, many things left unsaid in this letter, incidents both amusing and horrifying, and anecdotes and what not, but I hope this is enough for a while.

With love to all, I remain,

Affectionately,

Louis

Address:

Air Service, Gen'l Hdqrs.

A. P. O. 706, American E. F.

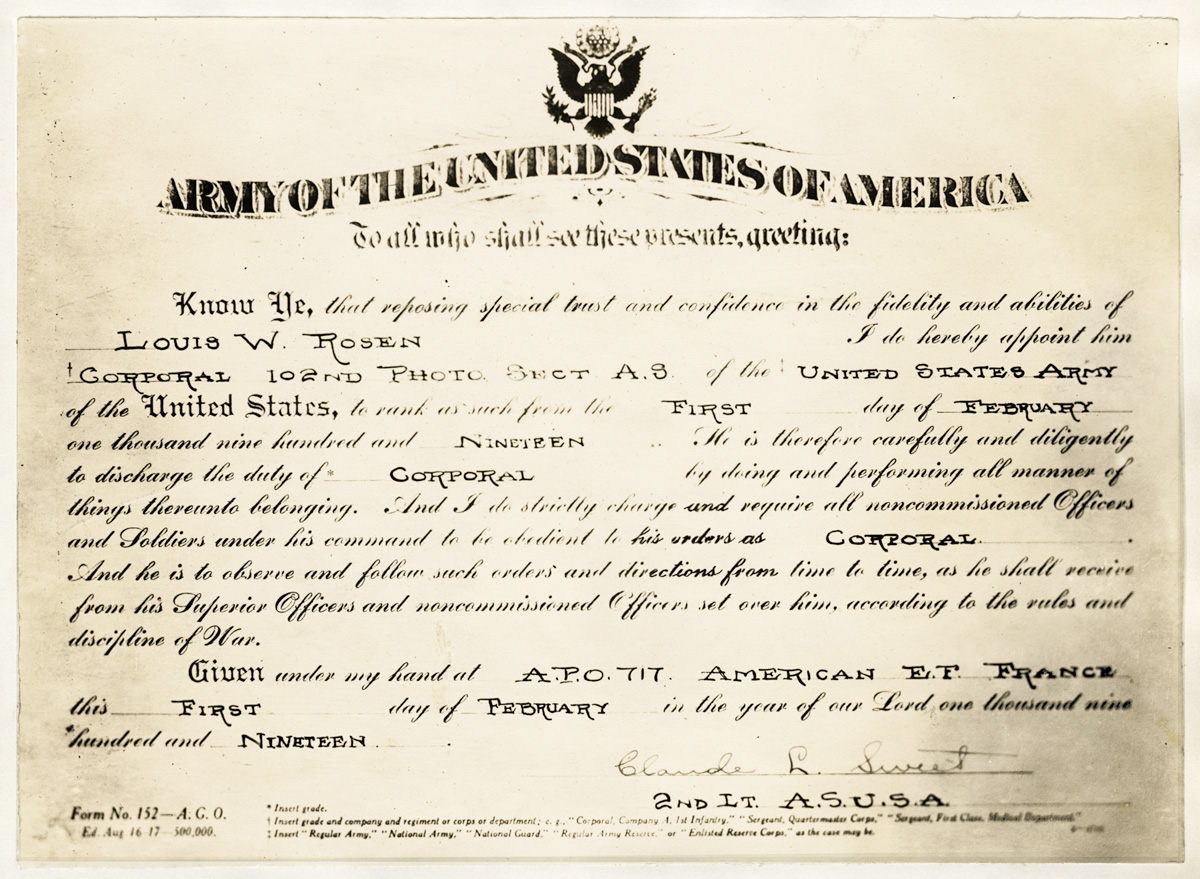

HEADQUARTERS, PHOTO SECTION

AIR SERVICE

A. P. O. 717, American E. F.

France, February 17, 1919

Dear Folks:

I was in hope of being home by this time and telling you more of my experiences in the American Expeditionary Force, but as this delay has occurred, I thought you would be interested in reading a supplementary account of what I have gone through, touching matters very little of which was mentioned before in “Dad's letter”, or as you term it, “17 page history”.

Even in this letter, I could hardly write everything, and many important things will slip my mind or in fact intentionally be omitted for want of both patience and time. From what I have stated before, you have a pretty good idea of my general movements, and I therefore can refer to them with little explanation, knowing that you will understand my references intelligently.

On the Vaterland or Leviathan coming over, we had but two meals a day, but they were good. Yet, that is all I cared for under the conditions we were traveling with a limited amount of freedom on deck. The meal service was handled quite efficiently, considering that there were over 12,000 men to feed at each meal. We ate in what was formerly the First Class Dining Room. It is the size of a large ball room and in height it extends through a few decks, allowing sufficient breathing space. We ate standing up, saving much room and confusion. That same room was cleared each night for moving pictures. Our bunks were very congested, the aisles very narrow. Every available inch was used up for quarters. We slept four cots high. They were so close to each other that one couldn't even sit up; I had to bend at an angle of about 45 degrees. Before we started out, one fellow shot himself intentionally in the foot and as a result all our ammunition was taken away for the rest of the voyage. There were rumors of another fellow jumping overboard, but I personally never confirmed it. While at sea, in the preparation of one of the meals, ground glass was found in the mince pie before being dished out, and as a result all the baking for that meal was condemned and not used. I know this to be a positive fact because our own cook who helped in the kitchen witnessed it all. Every afternoon we had Abandon Ship Drill, taking with us to the deck our life preservers properly adjusted, one blanket and a canteen of water. There was no lowering of the boats, only a standing by. Two days before we reached our destination at Brest - although the guess was, even by the sailors, that we would land in England - the break of day revealed four United States Destroyers convoying us. It was quite picturesque to watch them, two on each side, dart through the water. Standing from the top deck of the Leviathan they looked by comparison like little bugs cutting hither and thither in a zig zag course all the time at a tremendous speed, shooting away from us for a little distance at an angle, then coming back to us. So they followed us for two days and two nights, before which time we sailed all alone.

The last night was quite an ominous one, for we were passing through the most dangerous part, right through the submarine zone. While on other nights we slept partly undressed, that night we were specially cautioned to keep all our clothes on under penalty of punishment and also our life preserver adjusted and tied. Everybody had to be in his bunk at 10 o'clock and no loitering was allowed anywhere. The officer in charge of the ship in a deep voice went throughout the halls uttering the necessary regulations for us to follow. The port holes were closed tight as usual, and consequently with the crowding and the way we were dressed in bed, a Turkish Bath was like Iceland in comparison. Special guards were placed that night to watch every port hole. However, except occasionally for the sudden stopping of the boat or swerving from her course, nothing was heard or felt, and the next morning we found ourselves at anchor in the Harbor of Brest with the soil of France right in front of us. During the week we were supposed to rest up at Pontenezen Barracks in that town, and in line with that we had frequent hikes and marches with the band playing, going through neighboring villages and making quite a hit with the peasants.

The train trip from Brest to the Artillery Training Camp at Camp De Souge, 14 miles from Bordeaux, consumed a few days and nights. The train would stop frequently between and near stations for various personal accommodations. We had no portable kitchen with us on this first train trip (otherwise known as a rolling kitchen), and so to make up for the dry stuff we were eating all the time. at intervals in the large stations we would be served with coffee. I think only in one instance did we strike a Red Cross service and their coffee was fine. The rest were by the French. No milk, no sugar, yet of course it was coffee, and being hot was quite welcome. Sometimes in the middle of the night a particular station would be reached where we could get the "coffee", and with the chill the night brings on, none of us ever turned away that drink. We were early-comers in this war, and no doubt in the ensuing months more Red Cross stations were established. At these various stations, night and day we met French soldiers who were incapacitated from the war and heard many a horrible tale of what war was and what we were in for.

At Camp De Souge near Bordeaux, I had comparatively speaking, my easiest time with the 77th Division. The unit having arrived fully equipped as a result of all that work put in at Camp Upton; there was no rush at any time on the equipment proposition (except toward the end on the harness equipment), and I could take my time about it. The assignment to this work kept me off all details for the various kinds of work, something that no private enjoyed. I have been in the kitchen only one day, on a Sunday at Camp Upton, and I nearly missed that. The schools for training there were quite interesting. They tried to make the course as practical as possible, but the knowledge was necessarily cramped on account of the brief time of two months in matters that take years to learn efficiently. We went to school every day, including the officers. It was interesting to watch the latter, from colonel of the regiment down, file by on the road with note books in their hands, each morning, like a lot of school children. We spent the time at lectures and then out in the open at actual work in constructing telephone lines, poles, trenches for telephones, etc., and in setting up and maintaining communication between the Observation Posts and the guns when there was practice on the range in firing the 6 inch Howitzers we were using. We also had many lessons in signaling by buzzer, by flags and by projectors. The latter is the flash-light method and we would go off in the woods, stay apart at distances and flash messages to each other. Sometimes a French peasant would pass by with a basket of oranges or some good-for-nothing cake, and signaling would cease instantly, except to notify the distant party to come hither. A picnic would take place until it was time to go back to the barrack, and eat some slum. There were about three examinations given at the school, but apparently to stimulate some kind of competition, the fellows, as usual, had their note books with them. There were no desks to lean on for the purpose of writing, so we used the note books for that purpose. The hint was strong enough, and if a fellow kept his notes up to date and didn't get over 90 per cent, it was because he couldn't read his own handwriting.

The train trip from this camp at the end of two months to the first battle front in the Alsace-Lorraine sector had with it about the same experiences as in the previous trip, except there were horses and wagons to deal with and that just topped the climax for exertion. The horses used the same kind of cars we did, only by virtue of their size only 8 could be fitted in, just as the sign read. However, a narrow aisle was left and in that aisle in each car two of the fellows were assigned to sleep and stay there all the time, to take care of the horses' wants in every way. Luckily, I was never chosen for that job, although there were many cases where the fellows refused to be relieved when they saw the congestion we had in the cars without the horses.

We arrived in Baccarat under cover of darkness. There was an air raid in that town just a few nights before. Just as we started to march through the town about 3 A.M. (after getting all the horses and wagons off the train in that pitch darkness) a light was seen flashing from one of the houses, and one of our officers had it surrounded on the assumption it was the work of a spy. The military police (M. P.) came right up and the matter was turned over to them. What happened later, I never learned. We marched through the town worn out and broken up from the"feather-bed" ride. With the number assigned to each car, there was actually no room to sleep in those cattle cars. I would very often wake up and find my head resting on the edge of some body's heel (none of us undressed) or sole, and had to lie cuddled up in the most peculiar kind of contortion.

It was after detraining at Baccarat that we got the first glimpse of enemy aircraft observing right above us, and many a battle did we witness in the skies. We camped in the woods under the cover of many trees, to avoid being observed. That same day, two of our fellows were shot at different intervals by some evidently hidden sniper, as we couldn't otherwise account where the bullets came from. In both instances they missed their mark. The next day, our Headquarters Company was separated into three battalions, and we each marched off to our separate sector of operation, all of us, of course, remaining in the same section of the country. My third battalion reached a place in thick woods covered with large and beautiful pine trees, near the town of Maisonettes. There were about 30 in this battalion. Together with Major Moon and several lieutenants, we constituted Third Battalion Headquarters, taking in the operations of Batteries E and F. The Major, however, stayed about three miles away from us. In the two weeks we were there, we laid, up and back and around, a distance of about 25 miles of telephone wire, crossing hills and dales, and connecting the batteries with our headquarters, the Major, etc. This had to be done with a lot of patience and extreme care, because every single day the Boche planes were hovering above us in plain view, and we had to keep dodging under trees with our reels of wire to avoid disc1osing our operations. The antiaircraft guns would would be working all the time, and it was quite picturesque to see the puffs of smoke around an enemy plane or planes as she or they would move along to escape the fire. One could count at least 30 puffs around each plane and it often seemed like so many airplanes. Never did I see a plane shot down by an anti-aircraft gun. The chances of getting a plane in that way from ground fire is very, very slight, but it does accomplish one good purpose: it makes the pilot fly very high and get away without much delay, to avoid being hit, and consequently he cannot get much valuable information of what is going on below.

Our third battalion had the distinction of firing the first National Army gun, and it was in this Alsace-Lorraine sector. Right at the start a German was found wandering in Baccarat, and when picked up and examined, it was found that he had escaped from the lines opposite us. He was very hungry and after being fed, he was taken up to the Intelligence Office and questioned. He gave the information that a certain church opposite our lines was being used by the Germans as a munition dump. The following night (Saturday) one of Battery F's guns was secretly shifted from her then permanent position to a position some little distance away. From there she blazed away at the church, and the fire that went up after the church was hit left absolutely no doubt in the minds of our officers that it was the result of bursting shells within. The gun was then brought back to her original position - the original shifting being made so as not to disclose her position and later draw counter-fire and perhaps be hit. I met that gun the next day and patted her on the back, for these instruments after a little work almost assume a human existence, and are very much personified by the crew.

That sector at that time was what we called "comparatively quiet", but a thing of this sort of course aroused the enemy a little bit. Sure enough, on the next night there was a genuine air raid. Very few air raids accomplish just what they set out to do, and the result was that several Frenchmen were killed about a mile away from us. That night, as we reposed in our pup-tents, we could hear those planes buzzing above us, never knowing what was going to happen and where the bombs would land. We could detect a German plane by the double sound of the motor as that was quite distinct; our planes had a continuous buzz. At any rate, when there were planes floating around above us, in nine cases out of ten they were German. There is one thing about a plane: you will always know that it is above you and out in the silent country it has to be extremely high for the sound of the motor not to reach you. In that same sector the 308th infantry had about 50 of their men trapped in a trench with uncomfortable results.

As stated in the other letter, our detail took turns in guard duty as among ourselves. There were three shifts: 9 to 12 P.M., 12 to 3, and 3 to 6. I started off on the second night, from 12 to 3. All the telephones were not set up as yet, so there was no switchboard to take care of in addition. All I had to do was to keep my eyes and ears open, or better still, not fall asleep. The next time I was on guard was from 3 to 6 A.M. About 5 A.M. I started the fire for the cook and some water boiling for the coffee and an hour later waked him from his sleep to prepare the morning chow. The last time I was on guard was from 9 to 12, and it proved to be the most exciting. (These last two times, by the way, my position was near the switchboard, which was already in operation, installed under a clump of trees and with many bushes surrounding it to avoid detection.) It was about 11:15 P.M., pitch dark, no moon being out nor any stars visible. The boys were all asleep around me scattered among the trees in the immediate vicinity of that thick forest. One of the lines on the switchboard was to a station secretly known by us as Red Central, through which we could get connections to distant lines if necessary, that is, lines of the Signal Corps running to other and far away units. Every half hour at night Red Central would call up and simply check up that the wires were working. The reason for this is to make sure no one had cut them and if anything had happened to make the repair so that when any urgent use was necessary not to be left in the cold at the wrong moment. So, in that darkness, until 11:15 P.M., all that disturbed me was this regular call at intervals. We had a side connection, so that when the buzzer would drop, a tiny lamp would light all the time the buzzer was down, enabling us to see and make the connection - as otherwise no lights were allowed. (and this was very dim and only for a moment). The response would be "Orange talking. O.K., good bye". (Each station had a code name).

At the time I mentioned a call suddenly came in from the Commanding Officer of Battery F. As I answered the call, the Captain said, "I hear signals in the direction of the Infantry lines, which sound very much to me like signals of a gas attack". I snapped right out and said, "Captain, what do you want me to do, spread the alarm?" He said, "I think it would be advisable for you immediately to call up the Battalion Commander (the Major) and get his instructions and then immediately get in touch with me again." I quickly called up the Major, the Adjutant, however, answering for him. I told him briefly what the Captain of Battery F said. He told me not to spread any alarm instantly but be on the alert and wait for more definite signs, suggesting that if the matter became serious Red Central would notify me also and I would then be sure.

Well, if this thing had really developed, I would have been in some fix, for at the psychological moment I would have had to do about a dozen things at one time and yet protect myself. It was up to me to fire a few shots and wake the boys; to bang away at an empty brass shell case hanging nearby for that purpose; to telephone to the Commanders of each battery and to the Major at Battalion Headquarters; and in doing all this, if there were gas coming too close to us, I was to protect myself with the gas mask. The latter is generally effective when one can remain motionless, but to maneuver around and accomplish things at the same time, it is a very big handicap. I just sat silently waiting for another call or some other sign, in the meantime preparing myself for an emergency. I laid that revolver of mine right down in front of me and adjusted the gas mask against my breast in the alert position. The seconds passed into minutes, the minutes into five minutes, and so on. When 12 P.M. arrived, the time I was to wake my relief. I hopped off in the direction of where he was sleeping and got him up in quadruple quick time. The poor nut, while he was unconsciously rubbing his eyes, I was filling him with all kinds of ghost stories of the gas attack that was to be and had not yet come on, and told him to hurry off to the switchboard. As he went ahead, I darted into my pup tent with a sigh of relief at least for the responsibility that was lifted from my shoulders, and from the bottom of my heart wished that fellow good luck. In a few minutes' time I fell asleep, and the first thing I knew the Sergeant Major was blowing the whistle for breakfast. Hence, nothing had happened, except all this excitement.

Two days tater, while I was sitting under a tree and writing a letter in pencil, our telephone officer rushed up from the switchboard yelling at the top of his voice to the Sergeant Major to harness the fastest horse on hand for a so-called Paul Revere ride. Word had come that information had been received through secret channels that at 3 P. M. an enemy air raid was to take place over us. That time was quite near and we all made a rush for our tin hats and gas masks, this being the proper dress for such a pleasant party. We sat there looking at each other and waiting. We had not yet constructed any dugout and simply trusted to luck. Again, the seconds passed into minutes, and the minutes into hours, but nothing occurred and the only thing accomplished, so far as I was concerned, was a letter or two. I cannot remember just to whom I had then written.

It was toward the end of our stay in that sector that I received the first encouraging news of the war. While passing through the French town of Raon-l'Etape (in the Vosges) on a trip from the Major, a French officer told us that the previous day about twenty odd towns had been regained and about 10,000 prisoners taken. He got this information through a wired message. None of us believed him. Sure enough, it was in the papers the next day and from then on the news was of a brighter nature. The drive back had begun to mean something. However, that drive needed men and all else all the time to keep it going, and so our expectations of remaining in that sector for a few months was brought to an end after a two weeks' stay. Then word came to our detail from the Major's station to move on the same day - some short notice believe me - and to pack up and join him with the batteries a few miles away. Talk about work! My!! As we were leaving, a French unit was taking our place from the Champagne region, and they were amazed to find that we had not as yet constructed any dugouts. but lived in tents hidden under the trees. We were evidently doing it in the true American way, although the truth is we had not found time to attend to it and install such "improvements".

Right here, before describing the new move, I will say a few words about our experience with the Salvation Army in this sector. On two occasions our cook was short of this or that. These people had a hut in Neufmaisons, nearby. On one of the occasions they loaned us, on our word, a quantity of sugar which indeed was rare and otherwise impossible to obtain except from the Quartermaster when they had it; and on another occasion, when we were particularly short of rations and it looked like nothing to eat, they went to the trouble of baking for us a large pan of cake, enough to satisfy everybody. Every day we could get their crullers and some drink with it and everything that we bought was given in quantity and one felt he was getting his money's worth. Their treatment in general was splendid. At that time, being isolated as we were in one particular sector, I thought we had simply been fortunate in striking a good branch (this was the first experience with them), but sure enough, later on in the ensuing months, when I met fellows in other sectors and circumstances, they had the same opinion and praise on their lips, and I then became convinced that that was their conduct everywhere. They deserve all the praise they can get and also all the support they can get, and I say this very sincerely. Through experience, I cannot speak in the same way of the Y, although I think the intention was there, but that it was simply a case of gross mismanagement.